When I was young, I never dreamed that one day, fibbing to my mom would be better than telling her the truth. Instead, I strived to dodge that age-old, childhood taunt: Liar liar pants on fire.

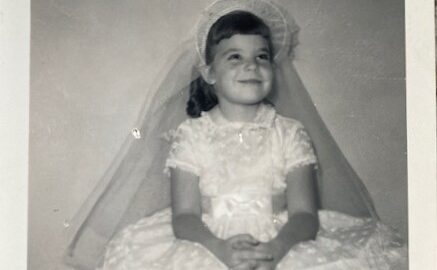

I’d be lying now though if I said that fibs never crossed my lips. In fact, before I aged into double digits, I would silently breathe that insult to myself whenever a Catholic priest slid open the panel that separated us inside a confessional. Gazing through the shrouded window at the shadowy figure opposite me, I always spoke in a hushed tone, praying that whoever sat on the far side of the confessional could not hear my litany of sins, including my lies.

I recited the same list and assigned a corresponding number at every telling. I fought with my brothers and sisters nine times. I disobeyed my parents seven times. I lied eight times…Though I did not keep a tally, I was certain some of my infractions numbered ten or more. Hence, liar liar.

Fast forward fifty-some years.

I hunkered in assisted living with my eighty-nine-year-old mother after she broke her pelvis in October 2020. Her senior living community was on lockdown due to the COVID-19 pandemic, but I was allowed to be her essential caregiver during her rehabilitation period. Throughout my fourteen-plus week stay, her bones healed. Sadly, her dementia progressed.

Mom’s grasp of reality fluctuated. Sometimes she knew who I was. Other times, she thought I was her friend Shirley. One afternoon, my sister Laurie called while Mom and I were eating lunch. During their conversation, Mom said, “No, Karen’s not here.” She listened to Laurie for a moment, then turned to me with a quizzical look and asked, “What’s your name?”

“Karen,” I said.

Her face softened into a smile. “Oh, you little pup!” she replied, and her words and mirth made me laugh.

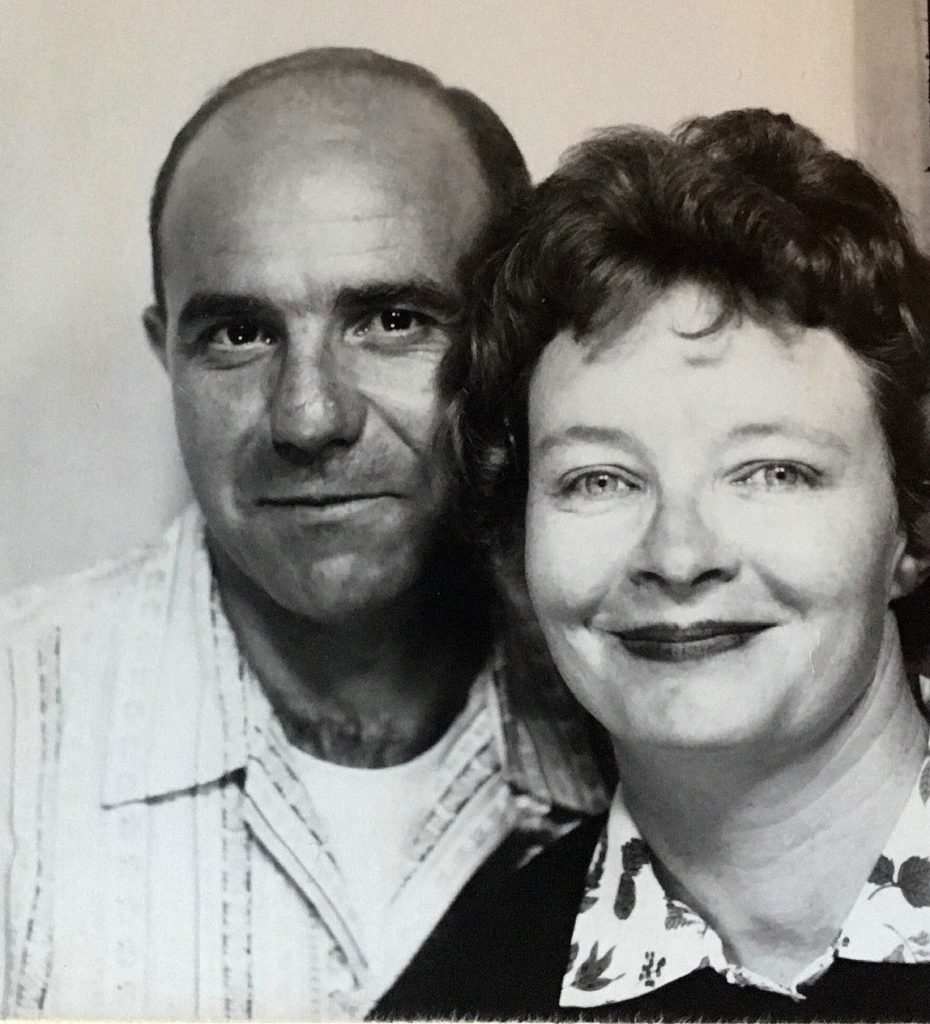

Most days, Mom remembered that our Papa had died. The large, foam-backed banner that sported his picture, birth and death dates, and the words, “Forever In Our Hearts,” was propped atop her dresser. When she made loops with her walker, she’d often smile and say, “Hi, Pops,” throwing in an occasional, “Pray for us.”

After she regained her strength, we made weekly outings to a coffee shop drive through on our way to visit Papa’s grave. On the fourth anniversary of his death, we were parked in our usual spot at the cemetery. “I haven’t seen your dad in a long time,” she said. Sorrow laced her voice.

I replied with the gentle words that had softened her sadness when I’d needed them before. “Papa’s in heaven.”

“He died?” she wailed. “Oh, Dan. What did I do to you? I’m so sorry…”

I longed to dial back my words.

I had recently learned about “therapeutic fibbing”—bending the truth to match her reality—and “redirection”—shifting her focus. In hindsight, I desperately wished I had used one of those techniques that day and struggled to give myself grace.

Two-and-a-half weeks later, the senior living community hosted a reading and author’s chat for my novel Perimenopausal Women With Power Tools. Mom sat in the front row, alternately beaming and dozing. Guilt haunted me, knowing that, like my protagonist, Beth, I too was harboring a lie of omission—“the worst [kind],” according to my eighteen-year-old character, Kate.

Unbeknownst to my mom, she would be moving into memory care the following week. I’d stay with her for two days, then return home. My heart was breaking.

I spent several fitful nights lying beside her in her queen-size bed, agonizing about leaving and wishing for clairvoyance. If I knew Mom’s days were numbered, I would power alongside her until the end.

But then moving day arrived. I chased sleep for two nights in memory care, tucked into a rollaway at the foot of her twin bed. Every cell in my body ached at the thoughts of saying goodbye.

I waited until the last minute to tell Mom I was leaving. She was in the living room, watching a musical with several of the ladies. I said quiet goodbyes to staff and some of the residents, then squatted in front of her chair. I still had vacation time, plus hadn’t dipped into the Family and Medical Leave Act, but I couldn’t admit that staying and watching her decline was so damn hard. Instead, I lied and said, “I have to go back to work.”

“You do?” Anguish filled her face, and her eyes puddled as she grabbed my hands.

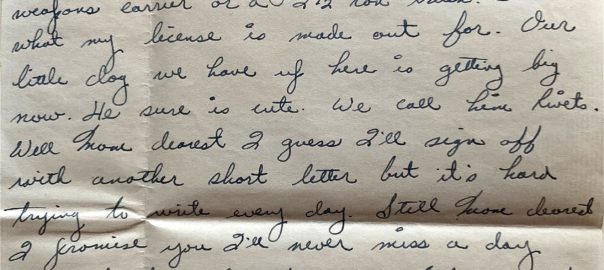

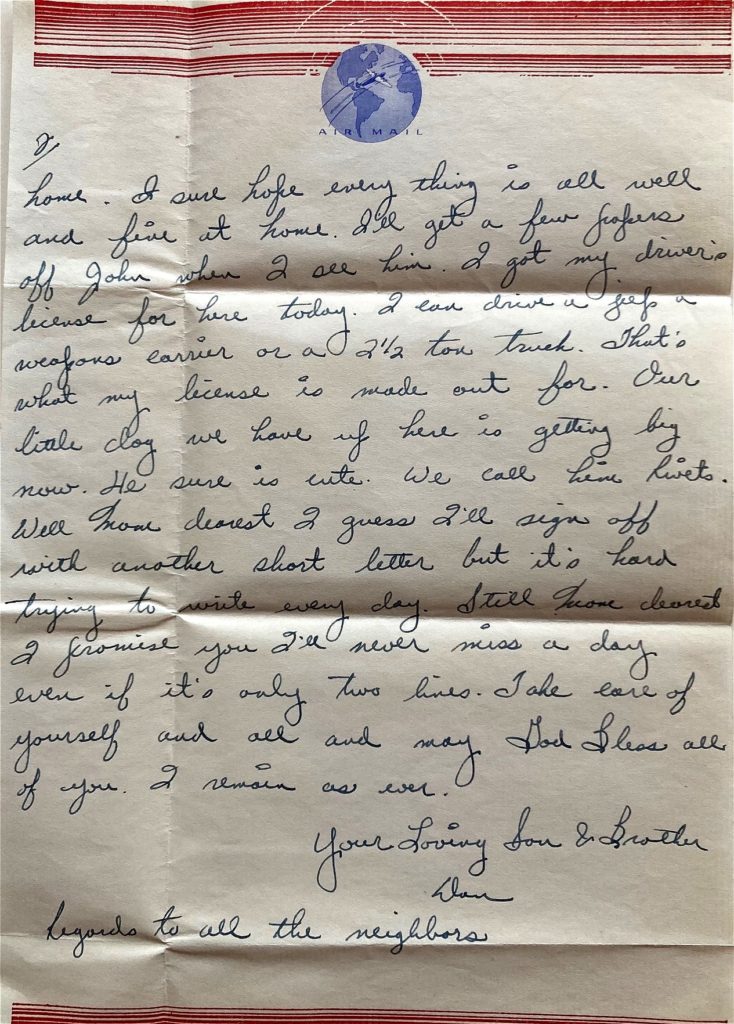

“I do.” I straightened, then added “I’ll be back,” and kissed the top of her head through my mask. “I’ll call you when I get home,” I said, knowing my standard words were a fib now too. “I love you,” I managed, unable to stop the quiver, but turning before tears streaked my cheeks.

I did go back, including for a weeklong stay and some other overnights throughout the next twenty-six months. During that time, Mom graduated from hospice care twice, then was referred a third time the day before she died. I was blessed to be at her bedside when she exhaled a final, peaceful sigh.

In truth, I’m grateful for more than sixty years of memories.

I’m also grateful that, whether my mom is somewhere over the rainbow or on the other side of the veil, her journey through dementia is over and she’s living her new, best life.